Interviewed in Zagreb 24th September 2010

Lada Hršak is certainly not a conventional ‘office architect’. She designs independently or in a tandem, works with larger practices, builds and participates in conceptual competitions, works hard on education all over the world, uses other forms of architecture like personal exhibitions. This wide range of creative experiences shows an active choice of working contexts and a lifestyle that guarantees mobility and a free choice of themes. Despite such heterogeneous interests, Hršak does not leave the borders of architecture as a discipline, but concentrates on how to articulate space with architectural means and methods. Hršak believes that the concept, the interpretation of a theme and the architectural elements are equally important within the design process. Her basic ideas are marked by empathy towards reality and the ability to conceive imaginative and culturally open project scenarios.

ORIS: Do you see the 1980s as a formative period, a source of some of your professional or even personal identity? During the 1980s, Zagreb was a lively place, developing its cultural life in institutional and non-institutional settings.

Hršak: My sources can be found not only in the 1980s, but also in the 1970s from the Zapruđe neighbourhood, where I lived until the age of 15. The idea of an unlimited modernist space, the pleasure of spending time on a wide road with few cars surrounded by meadows, all this was a fundamental influence. ‘Westerners’ believe that modernist complexes like New Zagreb are a kind of ghetto with immigrants that cannot read or write. When we lived in Zapruđe, our neighbours included a medical specialist, a music school director, a waitress, an electrical engineer and a glass blower. For example, there were numerous garage bands in the 1980s, but they did not originate in ghettos. Those boys lived in large, beautiful apartments in the centre, but they rehearsed in garages in New Zagreb, it was an integrated urban culture. I think that the coexistence of what the West would define as alternative and non-alternative lifestyles was a specific feature of our culture in the 1980s. I believe that the ‘West’ would love to go in that direction, but it encounters many obstacles.

ORIS: After graduating in 1992, you founded an architectural group called Desant, which seems to be the architectural continuation of the atmosphere of the 1980s.

Hršak: As far as I know this was the first female architectural group in Croatia, Desant included Žana [Jakopčić], Alida [Janković], Tanja [Gabrić Lacko], Nada [Pavić-Bralic] and me. We designed numerous installations, such as our ‘soft wall’. At the time, it was fashionable to hang out in a club called Fanatic, where everyone leaned against the wall. We thought it would be great if we made a cushion wall for the club and cover it with rubber. The softness of a hard wall is an oxymoron, we were into oxymorons then. We made a cushion as a modular prototype and realized to keep elasticity the cushion had to be rubbed with Nivea cream regularly, since the rubber was not elastic enough. Then we started thinking about a better material and the project never got realized. Ten or fifteen years later, a ‘soft wall’ was made by NL architects in the foyer of the Cinecenter cinema in Amsterdam. I still elaborate Zagreb-based themes and concepts, which we set up in the late eighties and early nineties, but now translating them in the present time and location.

ORIS: In your conceptual research, you looked for architectural possibilities where you do not literally build things, but recognize specific urban situations and provide a micro-response, so to speak. Croatian architecture did little research in the area of small-scale experimental interventions, taking absolutely no notice of the work of Desant.

Hršak: Those were threads in the urban tissue of Zagreb, in real life. Absurdly enough, only our best friends knew what we were doing, since we were quite unaware of the public, despite the fact that our projects dealt with the public realm. Instead of an office, we had a mailbox that we ‘illegally’ set up in the entrance of a building in Teslina Street. It was a completely nomadic setting, a mailbox instead of a site.

ORIS: Your mailbox is related to the tradition of mail-art, which was then revived in Zagreb by Greiner & Kropilak and others. But you soon went to the Netherlands. How did your experiences from Zagreb help you in your new environment?

Hršak: I went to the Berlage Institute in 1994, which was a crucial time in my life. Everybody was there, Rem Koolhaas was lecturing, we worked in the studio of Elia Zenghelis. He appeared like the ‘old guard’ and we, the ‘young conceptual thinkers’, thought he would be thrilled by our proposals. It did not happen at all; instead, he said: Can’t you do better? It was a great moment of learning. We learned to think differently, it was like taking a design and rotating it by 90 or 180 degrees. In Zagreb, we had learned to analyze in a linear way, to reach a conclusion and turn it into a final concept and a project or proposal, for better or for worse. But Berlage made us jog our brains, I believe, and showed us how to solve the same problem from very different angles. I studied under two deans: first under Herman Hertzberger and then under Wiel Arets. It was interesting to see the two kinds of thinking, the two circles around those two men. Arets brought many contemporary, trendy, parametric design methods.

ORIS: It is interesting that Wiel Arets gathered parametric designers, which is not quite close to his design work. I suppose he estimated that the design methods based on new digital technologies were an important development in architecture and that the Berlage Institute had to be at the forefront of such research. It is the idea of a continuous self-reform of schools.

Hršak: Yes, this is the intelligence of education.

ORIS: I suppose that Hertzberger was more reserved about such approaches.

Hršak: Absolutely. He even had strong doubts about some of Koolhaas’s ideas, but it is not about accepting or rejecting, Hertzberger has an unquestionably vital way of thinking that he can rely on, to openly say what he thinks without calling it good or bad. Interestingly, Kenneth Frampton delivered lectures at the beginning and at the end of our studies. At the end, he would say the opposite of what he had said at the beginning. Intrigued, his smart students asked: What is this now? Before you stated the opposite, you are being inconsistent. He would reply: No, every mind has the right to develop and change opinions, this is what intellect is about. It was another moment of learning: there is no need to blindly insist on a single course.

ORIS: Was there a pronounced change at the moment when Hertzberger was replaced by Arets?

Hršak: Under Hertzberger, we did not use computers so much. Instead, we used the copying machine, although everybody was concerned about the topic of the new digital age, the virtual age. In principle, we were still using analogue methods. Arets procured a pile of Macs, he provided us with computers, scanners, 3D programs that hardly anyone knew how to use. We started creating diagrams in Photoshop with an analogue logic and those are some of my favourite diagrams, they have a particular beauty. One way of thinking can curiously translate into another. This is gone now, since we know how to use the programs and do not have the discovery of the unknown. Recently, we watched the first ten minutes of Wenders’ film Until the End of the World with our students, because the topic of our entire semester is the street. Claire, the main character, travels from Venice across the Alps, gets lost and arrives in Paris, where you see the real and virtual image of Paris at the same time. We want to achieve that combination of virtual and real.

ORIS: You have described your experience of the particular atmosphere in Zagreb in the 1980s. Then you went to Amsterdam. Did you feel that you moved from a post-socialist context into a multicultural and international context?

Hršak: Yes and no. We found ourselves at the Berlage, a separate state inside Amsterdam. We studied together with Japanese, Koreans, Indonesians, Bolivians, and all kinds of Europeans. Together with the dean and tutors, those that taught us the most were our fellow students, with exchanges varying from culinary to intellectual. In fact, Amsterdam itself is a utopian city within Dutch society. The multicultural and open nature that we ascribe to the Dutch as a progressive people that navigated the world and chose the best – this is still the nature of Amsterdam. It was more open at the time, now it is more right wing, it has become more conservative. The Netherlands has had issues of identity in recent years. They were open, loved dialogue, trade, experiment and foreigners, which has been the long-term basis of their progressive society. Unfortunately currently a more xenophobic part of society attracts the media space. The Dutch have many layers of identity, but since those layers are printed in sand, it is hard to read them. Most people buy three houses in their life, so there are no situations where people say: I grew up here, my parents live here too. Maybe they are adrift because of their soil; it is hard to put down roots in sand.

ORIS: The exhibition at the Arcam centre in Amsterdam invited Dutch architects originating from abroad to show how they inscribed their culture and identity in the Dutch space. How did you tackle that theme?

Hršak: Architects working in Amsterdam with foreign ‘roots’ (hence the name of the exhibition) were asked to present the features of their work that are Croatian, Japanese, Turkish, Swedish, Portuguese, Mexican. It was a hard question: what was Croatian in my work? I like being a foreigner. When I work with the sense of being elsewhere, I have an idea of freedom. So I like living in the Netherlands, where I am both a foreigner and a local, because I have spent 15 years there. I presented three projects. One was the design of my own house, where the bathroom has a huge opening in the wall and the bathtub is practically in the living room. It recalls the time when I stayed at my grandmother’s and bathed in the living room; it was strong experience and I restructured this setting at my home. In that sense, the experience is Croatian. The other work, ‘Citroen’, is very dear to me. It questions contemporary identity by recognizing the historical context: a branding and development strategy for the region around Utrecht, which was the northern border of the Roman Empire. Our work repeats the ‘ancient Roman’ scenario of cultural export by introducing a new plant to the region, Poncirus trifoliata (trifoliate orange). By planting it on a large scale it provides a new character to the local landscape, has a nice fragrance, and is used for local products like jams and juices. The back label of these products sold in food stores contains information on archaeological sites.

ORIS: You also participated in a project that is related to the issue of identity relations. It is the Dutch embassy in Ethiopia, which won the Aga Khan Award. As a Croatian-born architect, you worked on a project that was supposed to present the Netherlands in a country on another continent. It seems that you wanted to deeply feel a unique new context.

Hršak: Yes, we completely immersed ourselves in Ethiopia, a country unknown to us, and it was a wonderful design and cultural experience. This building is inspired by the marvellous monolithic Ethiopian churches of Lalibela and therefore it is a monolith. It is built out of one single material, pigmented concrete. The outside surface is textured and rough, the interior has a lighter surface, and the floors are polished. When we were choosing the materials, we studied what Ethiopians were good at making and concluded it was concrete. Of course, it cannot be like Swiss concrete, because they are simply unable to do that, so we made the best use of what was available and obtained an expressive outside texture. In every project colour and texture are of great importance, and I often use only one colour and one texture. The colour of the embassy was the colour of the local reddish soil. Some people thought it was made of earth, but the colour came from the copper oxide we used as a pigment. The house is very rough, ‘edible’, and the windows act as a contrast, they are huge hydraulic frames placed on the façade with rubber joints. The building has only one window size, 1.20 x 2.40 m, and the doors are the same size rotated by 90 degrees, so that the mass is perforated with a single module. You can feel this. The building complex was built by a local contractor, the Dutch architects came for regular visits, but the local architect Rahel Shawl greatly contributed to the final result, since she went to the building site every week.

ORIS: When you think about the construction conditions in Ethiopia, it is something of a mystery, one thinks of the simplest possible technologies, of the avoidance of any complications or inessential details. The available building technologies are also a contextual layer that affects design decisions.

Hršak: From the beginning the design was formed under the local conditions with international intelligence. The contractor and local architect made a marvellous effort to achieve the necessary details (like the technologically challenging window frames). Ethiopia has a rainy season twice a year and more rain falls there every year than in the Netherlands. Therefore we applied Dutch/Arup know-how about water technology by collecting this water on the roof, directing it to the cistern and storing it. Since the Dutch live under sea level the embassy business would be also done underneath the water–roof. In the rainy season, the roof is underwater and when there is no rain, the texture appears as a carving in concrete. The texture of the traditional Ethiopian cross on one side and the image of a Dutch polder on the other. We linked the two images in Photoshop and applied them to the roof.

All in all, this was special achievement and the building was awarded the prestigious Aga Khan award for architecture in 2008.

ORIS: To continue with the topic of texture and relief, you also like the subject of textiles, pleats. Sometimes you use them literally in your interiors, but sometimes they are a metaphor, like the design of Rotterdam City Hall.

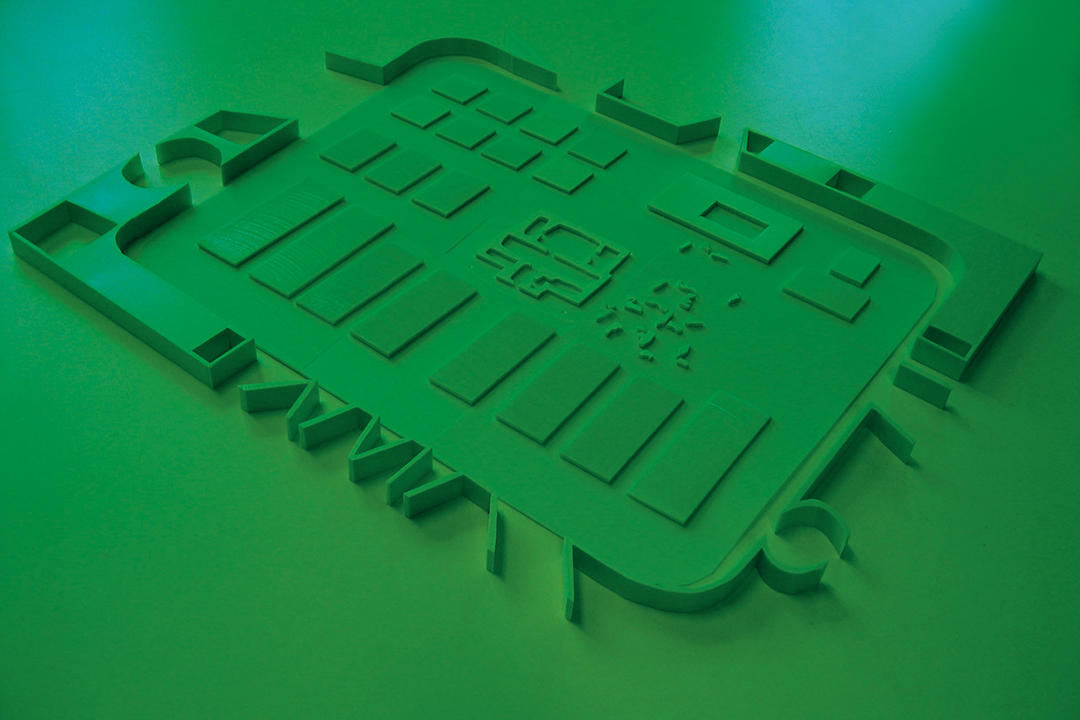

Hršak: In that project, it was important that half the programme was preset as the city hall offices, and the other half had to be added as a result of concept researching the meaning of the City Hall. The design consists of two houses, two fabrics, one horizontal and the other vertical. Since Rotterdam is an extremely multicultural city, the answer to the undefined contents was to propose commercial spaces for all the nationalities present. In that sense one waits for one’s passport in a Surinam bar, eating a ‘croquette’ sandwich or sitting in a Japanese tourist agency. The communications of the contents overlapped, one part had vertical connections like lifts and staircases and the other had horizontal (corridors). The project caused many discussions, interviews and positive reactions on the Rotterdam scene, it was quite utopian. As for the texture, it is a purely physical thing. I believe in the intelligence of the hand and the intelligence of the stomach, in the unconscious. Making my hand draw, since my hand is much smarter than my head. The façade was created intuitively, started by cutting foam to see what would happen. This manual work, a very analogue process, resulted in the model. A sliced model was scanned to provide the basis for 3D.

ORIS: This process works like action painting. You physically create not only the form, but also the concept. Still, what you call the analogue and intuitive process in your work includes reflection. The competition project of the artist’s house plays with the interpretation of this specific theme.

Hršak: A question arose: What is a studio for a contemporary artist? We concluded that the creative act lies in perceiving, processing and collecting the information. In a way similar to archivists. Therefore what they need is an archive. An archive can be a corridor with cabinets. We could not decide where it would begin or end, so we designed it as a squared circle. We were also intrigued by the issue of scale. The competition required eight pavilions, but they did not have enough money for eight big ones, so they decided to make everything in the scale 1:2. It is the question of how to handle different scales, so we designed openings with strange proportions, in any scale, 1:1 and 1:2. The entrance to the archive goes through a huge wardrobe. The corridor circumscribes an inner courtyard with a tree. This inner world is made of recycled materials like old doors and translucent materials; inside, the artist has dinners with his friends. The creative process happens and can be stimulated by collected materials. The volume contains a small slit that allows visual contact with the surroundings. From the outside, the building is camouflaged with mirrors, it reflects and negates its own existence.

ORIS: This project of reflexion takes us back to the issue of identity and the creation of a new Dutch landscape, which is related to the Gulliver’s House project. That project, similarly to Rotterdam City Hall, conceived a hybrid content.

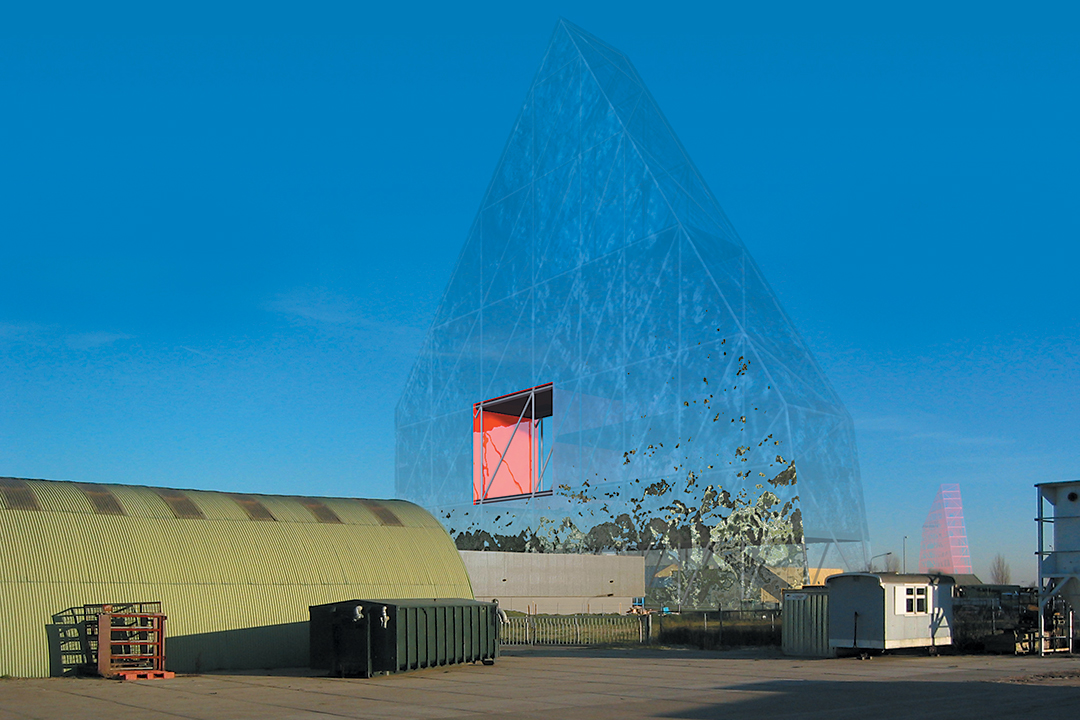

Hršak: The Dutch are famous for their tulips, keeping the bulbs in bulb sheds creating characteristic silhouettes in the landscape. Nowadays large business complexes dwarf the original sheds, and the question of this competition asked: what would be a new sign in the contemporary landscape? We reintroduced the silhouette landscape of small houses but since the scale of the landscape has increased, we blew up the houses. But only the silhouette, the height and length, so they became narrow. The basic programme of the lower floors are bulb sheds, while the upper premises contain hybrid contents. One house has a hotel, another has a therapeutic space for people with ‘burn-out’ with work therapy in the fields. Aside from the bulb storage the hybrid content units range from non-commercial to commercial. The façade is made of mirror glass louvres that must be opened for ventilation, but they also reflect the landscape. This is spectacularly beautiful in April when the surrounding tulip fields are in full bloom with its geometric Mondriaan-esque textures in strong colours: black, orange, purple, yellow... In this design we worked as film directors, using the architectural elements that amplify the current situation.

ORIS: The theme of relating to the Dutch landscape, its soil and nature, also appears in the design of the Visitors Centre.

Hršak: The Centre is located in the swampy area of Oostvaardseplassen, a nature reserve in the Netherlands. Its content is an information pavilion. Back in time the area lay at the bottom of the Zuiderzee and in the melioration works of cca 70 years ago it was dried out or made into polder. This polder would not ‘behave’ and it returned to a swamp again. Later the officials turned it into a bird preserve, while another part is roamed by wild cows, horses and deer. The area belongs to Natura 2000, a European network of protected nature resorts for preserving habitats. The project was made in cooperation with the landscape practice B+B from Amsterdam. This landscape is marked by endless, wide horizons above swampy land. As a reaction to this openness, our house defines a point by wrapping around a central space or a ‘base camp’ which is a primordial outdoor grouping. Therefore, the volume of the pavilion has the form of a ring that metaphorically remained at the bottom of the sea that used to be there but dried up. The ring is slightly inclined because the ground is not level. The pavilion is strategically placed at the juncture of the wet and the dry land pointing out the basic space dynamics of the landscape and articulating the cross section. The cross section of the house transverses from the dark enclosed underground section to the restaurant with wide views. An educational exhibition circumscribes the entire trajectory of the pavilion, where it touches other programmatic contents. The most interesting effect of the project is the combination of tactile, primordial and digital experiences of being in nature.

ORIS: Research architecture abandons functionalist and abstract thought about space and moves towards the notions of events and content groups. Such research often becomes increasingly narrative, interpreting ways of life or urban changes. Houses turn into scenarios, so you say that people suffering from anxiety can use your concept incorporated in the architectural design as a specific solution for their troubles. A design for an artist’s house demands from the architect to interpret what an artist is today. This interpretative component of architecture, that is not only a spatial concept but also a ‘design of the world’, looks typical for the approach researched by the Berlage Institute. But can an artist’s house be simply the house where the artist moved in?

Hršak: I agree with the criticism, it has both positive and negative sides. For example, one of the pavilions for the artist, where everybody made an effort to show their vision, is an ordinary shed which assumes that an artist would consider it important to have good light and to be tall. On the other hand, the nature of this competition was to provide a vision of what kind of space the contemporary artist needs. It is not a house for a specific artist, but a statement. A project for a specific client could have been quite a different story. Or maybe not, since it was first artists who reacted very positively to our pavilion. I believe that the ‘design of the world’ is not a suitable description of our approach to architecture. This can be a whole new discussion. We approach problems from a very local standpoint, where the global appears in a real space. Then things look different. We take our inspiration and methodology from anthropology and we ‘translate’ primordial elements into the present and into the spatial and cultural potential of the site.

ORIS: There are two diverging notions about the position and role of architects. On the one hand, it is thought that architecture can use its own devices to give a motivating shape to democratic society. On the other hand, architects have less and less influence as authorities in the formation of built environments. The smaller the actual influence of the architect, the larger the ambition to construct that influence, as an illusion at least, in specific constructions or proposals. The ambition to completely design events through architectural projects looks like Gesamtkunstwerk, but translated into the wish to turn the entire social reality into architectural content.

Hršak: Last year, the crisis revealed the illusory role and the inability of architects in forming a new image of society. In fact, late capitalism is destroying precisely the democratic, humanist features of the architectural profession. In that sense it is interesting to take advantage of the weakness of that very system and try to imagine a new reality, or a new social utopia. It will be hard. Saturated systems have fewer possibilities to regenerate. In the Netherlands, the ground itself has been constructed, so much has been thought out and built that there is less room for manoeuvre. In that sense, I see Croatia as a vital development area in the long term. We need it. While developing one must learn from earlier mistakes in that field in order not to devastate our coast like for example the Spanish. At the same time, we should accept and use contemporary ideas and methods to achieve space of high quality. For example: a developed consciousness of the values of the local culture, a long-term development attitude instead of quick cash, using sustainable systems and ecological thought, applying a combination of ‘bottom-up’ and ‘top-down’ development principles, etc.

ORIS: The Netherlands has an exceptional tradition of modern architecture, but also of territory organization, both utopian and pragmatic, which makes for a unique combination. Contemporary Dutch architecture in the last thirty years has become internationally prominent and largely influential. But although still producing high quality works, the Netherlands is not such a dominant centre of new architectural ideas as it was in the 1990s.

Hršak: I think that Dutch architecture is looking for a new way of expression. They are impressed by Portugal, Croatia, countries with a topography that they lack. When you have an exciting topography, you can make something quite abstract. Since the Netherlands is flat, the houses create a contrast or tension. Partly due to this Dutch architecture took the path of quirkiness, experimentation and joke at times. However, the changed social conditions force and allow the new generation to take things quite considerately, maybe less visually expressive, but better detailed. The craving for icons has changed form.

ORIS: Do you also educate others, and are you still encouraged by the motivating atmosphere of the Berlage Institute in the mid-nineties? What do the educational process and the exchange of ideas with students bring you personally?

Hršak: Sometimes one asks oneself how much is left to chance. For me, it is important to lecture at the faculty and keep in contact with curious young minds that work differently, they write computer programs. The new age, which was a matter of speculation among us at Berlage, is happening now. We are the in-between generation, we have analogue access and appreciate the feeling of touch that they might not have. When I teach, I try to confront these digital minds with the analogue way of work and model construction, to put them in contact with a texture. Currently, I teach at the Academy of Architecture (Academie voor Bouwkunst) in Amsterdam, at the Berlage Institute, but I also have curious exchanges, such as the one with the University of Auckland. It is interesting to check which social parameters overlap with the opposite side of the world.

ORIS: Your status and working method vary. Depending on the needs and circumstances, you are a freelancer or you cooperate with various practices, which is a dynamic and maybe unstable situation. Your choices somehow make you a professional ‘foreigner’ in various operating contexts.

Hršak: Could be. I like it. Professional architects can be compared to medieval professionals, travelling sculptors and architects. But I am currently founding a practice called DHL architecture (DH+HL=DHL) with Daniëlle Huls. We are putting together a visual ‘retroactive manifesto’. It is retroactive because our cooperation started in 1998, when we participated in a competition together for the first time. Curiously, this was the competition for the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb. This must be destiny. Right now, it is our only project in Croatia, but we surely hope that we will get an opportunity to change that.