Interviewed in Zagreb 23 September 2014

The Intermundia installation of the author Ana Dana Beroš and her collaborators is a part of the Monditalia exhibition set up in the Arsenale in Venice as part of the official programme of the 14th Venice Architecture Biennale in 2014. The multimedia installation and the research project which is focused on the southest Italian island of Lampedusa and the topic of immigration, questions political and intimate phenomena of the borders and their transgression. The installation was given a Special Mention of the Biennale.

Maroje Mrduljaš: Monditalia, a section of the Venice Biennale set up in the Arsenale, explores contemporary Italy. The exhibition consists of 41 individual works that are very different in medium and method, displayed in the premises of the Arsenale according to the territorial arrangement of the themes, from the north to the south. Hence Monditalia starts and closes with the theme of the national border. The section’s closing work is the Folder group’s Italian limes, depicting the instability and fluidity of the northern Italian border, which has changed over the course of time as a result of different circumstances and negotiations with the neighbours, and recently especially due to changes in the snow and ice in the Alps. The Italian border therefore shows how climate change, global ecology as and the advancement of digital technologies affect state frontiers, which are often perceived as an unchangeable given. Monditalia starts with your work, in which you problematize the issue of immigrants, taking up the case of the island of Lampedusa, the first place of contact on the path from Africa to Italy, Europe and everything we call the Western world. Your work should be read through the lens of social criticism and the question of migration policy, which you link to the labour market, but I believe your work to be interesting also for showing that a border is not a line, nor a dot, but a long-lasting process, the dramaturgy of an arduous and life-threatening journey, including the anxious wait in the detention centre, as well of the incertitude that follows if a pass through the administrative bureaucratic border is eventually acquired. There are thus multiple national and other borders, and their effect on the experience of an individual, especially those arriving from the other side, is very complex. From my perspective, all of us often find ourselves in the status of unprivileged immigrants arriving from the other side, in which we face transgressions of norms and borders, transitions from one status to the other, whether those contexts are entirely institutional or partly private. The immigrant’s situation is a story of fears, uncertainties, but also a story of vitality, especially of an almost naïve directionality toward the future. What made you interested in the theme of borders and immigrants? Croatia is currently in a liminal situation, in the eu, but outside the Schengen zone, a space in-between, both here and there or nowhere simultaneously, with the experience of a long-lasting eu accession process that seemed and still seems like a long stay in the purgatory of a migrant camp. Therefore I believe the Lampedusa experience can also relate to the current Croatian identity. To what extent does Lampedusa interest you as a concrete case, and to what degree as a broader rule and perhaps a metaphor? Can you explain the aspect of the post-human view you bring in to introduction of your research?

Ana Dana Beroš: The issues of illegal migrations, social inequality, the impossibility of belonging to a place, and their consequences in urban and social reality – these I consider to be key issues in Europe today, issues that we can no longer avoid in Croatia either. In the contemporary moment of the imperative of mobility, which is compatible with the imperative of work flexibility, the forced territorial migrations of precarious but very often highly educated workers are parallel to the wanderings and detentions of illegal migrants. Both of these permanently migrating masses are underpaid and intimidated work forces deprived of elementary human rights, including the right to work and lead a dignified life. It is necessary, then, to understand illegal migrants primarily as workers who regulate the gaps and fissures in the European labour market and respond to the systematically designed needs of the Western society, instead of perceiving them merely as derelicts in a naive search for a better life.

My interest in the theme of borders and migrants started in 2006, when for the first time I encountered illegal migrants in the Ježevo Motel near Zagreb, in an attempt to produce an architectural reconstruction project for this Croatian reception centre for foreigners. In the, at that time newly-founded, group archisquad – Division for an Architecture of Conscience, we felt this was an important social project in which we wanted to participate, but the competition was open for construction work only. Seen from today’s perspective, it was to be expected that priority was not given to the humanisation of this space for foreigners, but the concreting of the external, prison yard. Nevertheless, the centre supervisor gave us a tour of the site and we were able to meet some of the Ježevo inmates and hear their horrifying and very similar life stories.

Even beforehand, it remained imprinted in my memory how my mother, curator Nada Beroš, had in 2000 initiated and run the artistic project-in-the-making entitled Ježevo Motel. The development of the project bypassed the established cultural institutions, within the online magazine art-e-fact, whose first issue was entirely dedicated to illegal migrations and spoke of possible little utopias. On the other hand, the real family connection with migrations comes from my father’s side. A child from the Makarska littoral, at the end of the wwii he spent several years in the refugee camp at Sinai in Africa, which served as a temporary campsite for the evacuated Dalmatian population. Of course, during my own childhood I witnessed forced migrations, consequences of the Homeland War in Croatia and the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, when at the beginning of the 1990s the second-home complexes of the Makarska riviera were transformed into refugee camps and children’s towns, while the adults remained at battlefields.

In the curatorial research project Intermundia, which I started in 2013, the geopolitical focus was placed on the Italian island of Lampedusa. Research into the problem area of past and contemporary Italy was defined by the curatorial concept of the exhibition Monditalia. However, my research interest was of a broader range. The project depicts the case of Lampedusa as a metonym of contemporary detention conditions, a closed waiting-room at the entry to Fortress Europe. Lampedusa is a textbook example of an empty space arising at geopolitical crossroads, where socially marginalized communities are almost always being formed, be it newcomers or indigenous population.

The aspect of the post-human view which I mention in the research introduction refers to our constantly changing identities, to the uncertainty of the human existence. The concept of the post-human stems from the field of science fiction and futurology, and it literally stands for a person or an entity existing in a condition beyond the human. Yet this project does not focus on the question of the end of man as a consequence of the apocalyptic spirit of the time. It’s directed to the withdrawal of perspectives, of the foundations of affective solidarity, of empathy and connecting with others. In critical theory, the post-human position recognizes imperfection, the discord within a human individual, and the world is observed from heterogeneous perspectives, there is no objective observation. Therefore, the post-human individual is not a clearly defined individual, but somebody who can obtain various identities, and who understands the world from a multiple, heterogeneous perspective. Through an evocative sound and light installation and the research presented in a book, the project also tries to induce a layered understanding of the world within the observer. A layered understanding of the world, or rather, an understanding of the alternative worlds that surround us.

Maroje Mrduljaš: Your work entwines two narratives: the experiential-phenomenal and the political. The experiential, phenomenal, directly architectural, narrative is articulated through a spatial installation that replicates the experience of travelling in the bowels of a ship. We can somewhat link this segment to the tradition of artworks that use the destabilisation of normal spatial experience, like the works of Miroslaw Balka and others. The political narrative concerns research presented in the big book at the exhibition. This research includes various features such as a critical history of migration in Europe, cartographic depictions of early types of border-crossings, as well as interviews with various protagonists involved in the problem of immigrants on Lampedusa. This ambiguity between the phenomenal and the political is striking and didactic in your work. We can see how the politics directly affects the individual human and spatial experience. Therefore no spatial experience is completely innocent or separated from politics, and one of the effective ways in which the politics operates is precisely the control or normatisation of the spaces and the people in them. What is your view of this correlation of the political and the individual? Although your articulation and mediation of the problem seem logical, they are not typical of architecture. Can you also explain a bit further the genesis of the project and elaborate your position on the nature of the media and goals of architecture in general?

Ana Dana Beroš: I consider the correlation of the individual and the political to be inseparable, I believe such thing as apolitical individuals and apolitical spaces cannot exist. Civil and political rights are also inalienable human rights. The Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben describes the notion of bare life as the ultra-contemporary, sacrificial life of those with no ownership, a form of subservient citizens dwelling in the unqualified political underground. Although in the world reduced to markets and consumption the traditional understanding of the civil as politically sovereign is being transformed for everyone, the migrants are those that are experiencing the most radical loss of political rights in Europe today. Furthermore, Agamben claims that a refugee, an individual, marks, carries a political concept of borders within himself. If we reconsider our own body, we realize that at every moment of our life, even while we’re asleep, we choose the space our body occupies. These necessary choices we’re continually making, this violence of the occupation of our own bodies, carries great political consequences. To simplify, I’ll use the words of the young architect and writer Léopold Lambert, who wrote the introduction for the publication Intermundia: If we sit at the edge of a bed, we are not creating the same political intensity as that, for example, we crate while sitting in the street in the middle of a demonstration.

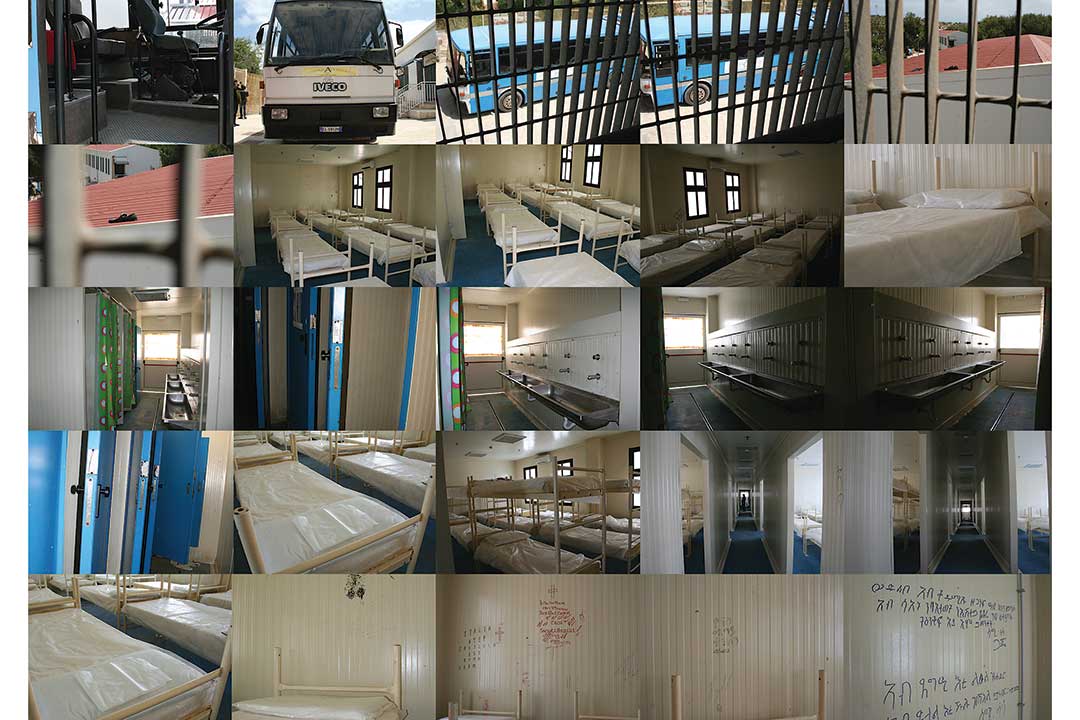

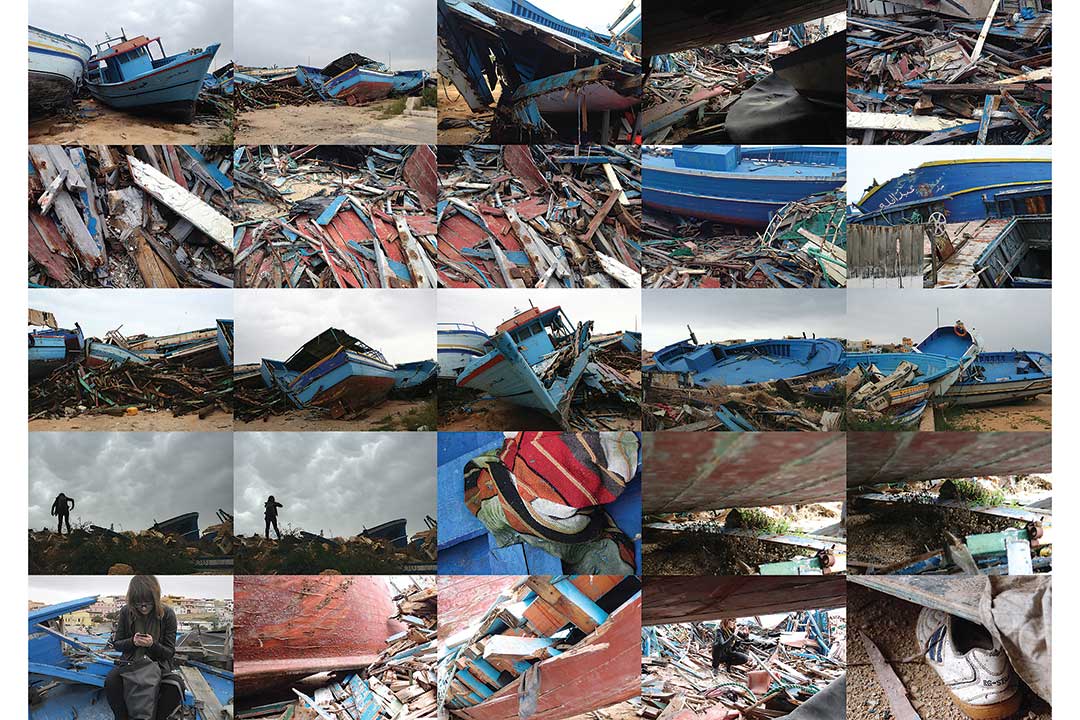

The genesis of the project Intermundia experienced several twists in an extremely short research and production period of only six months. Initially the project was supposed to deal with dry architecture, explore the typologies of refugee centers concentrated on the Italian territory, their urban and architectural characteristics and their evolution in the course of the 20th century. Due to the project’s exceptionally tight time and financial constraints, I decided to focus on the Center for identification and deportation Contrada Imbriacola on Lampedusa and travel to the island at the end of the world that is closer to the African mainland than to Sicily. The new circumstance was that it was impossible to actually get into the Center since it was being reconstructred during my field research, while its temporary tenants were evacuated to centers for illegal migrants on Sicily. At that moment a turn took place in my research and I focused on the experiences of the indigenous community, historically marked by trans-Mediterranean migrations. Alongside the standard photographic, video and audio recordings of my interviews with local protagonists, an integral part of the field research was the so-called field-recordings. Such as the sound of wind – documented in the old city harbour among the sunk, stranded ships from the Maghreb, a place known among the people of Lampedusa as the ships graveyard– served as a weft for the spatial sound installation at the exhibition in Venice.

As to the media that architecture uses, I can agree with many who say that architecture has nowadays become transmedial. We don’t create only in the offline dimension, in concrete and brick, but in the online sphere as well. All media are allowed, or rather necessary, to attain the goals of architecture. I dare say that the fundamental task architecture has is to articulate spatial thinking, thinking capable of asking questions about burning issues in a different way, hence of also creating a different reality. Architecture must offer a space for understanding of the existential condition of an individual and of society, and must also construct a foundation for a life with dignity. We know who we are, and where we belong to, precisely through human constructions, both material and intellectual.

Maroje Mrduljaš: In parallel to your project, Ivana Dragičević and Dinko Cepak have made an impressive documentary entitled Hotel Europa, also dealing with Lampedusa. You use the working material for the film in your work too, as well as the photographs of Ana Mihalić who explored the theme of immigrants in Croatia. You have activated already existing works and included them in your work. It’s not so much about the direct cooperation, but more about sharing. On the other hand, the designer Rafaela Dražić is an important partner for you in the project. What is your view on the fluid transfer of themes from one medium to the other, on cooperation networks in culture and architecture?

Ana Dana Beroš: I believe creative thinking can develop only in relation to other and different ways of thinking, and through the possibility of observing phenomena from different perspectives and divergent positions. Understanding such a multiplicity of perspectives is crucial for a fluid exchange, for complementing the mediums within a conceptual framework, within all cooperation networks. Besides Rafaela Dražić, who designed the huge book documenting the political narrative of the research, my key partners in the project are the multimedia artist Bojan Gagić and the sound engineer Miodrag Gladović. Working together under the name lightune.g, this duo is known by their innovative research in luminoacoustics, in which they transform light signals to sound images. For Intermundia they created an impressive light and sound installation that incites a direct reaction in the observer, immersing him into a fight for bare life. Through the strong dramaturgy of the two-minute-long act taking place inside the installation, together we have constructed a multisensory architecture. An architecture that does not rely to one-dimensional perceptive visual stimulus, but rather pulls us to itself through listening, suddenly pushes us away through deafening garble, only to bring us back inside the experience space.

Maroje Mrduljaš: You have participated in the most important world exhibition of architecture, and during the work on your project you have had the opportunity to directly cooperate with Rem Koolhaas and his associates. Interaction with leading figures of international architectural debate is no news to you, considering other projects of yours, such as the Think Space programme. However Koolhaas and amo represent the epicentre of present architectural thinking and set the standards. We can agree or not with Koolhaas’ viewpoints, but the fact is that he is the one who is opening new problem questions, exploring new architectural concepts and positioning architecture differently than all the others. He is simply in the position of forerunner, in which he would be with or without the media frenzy that’s surrounding him. What are your experiences of working at the Biennale? What is your view of Koolhaas’ role at the Biennale? I believe this Biennale is one of the most precise and the most consistent versions organised so far and that Koolhaas’ concept was set in such a way as to absorb even those who try to evade it. To what extent is the intellectual influence of Koolhaas implicitly or explicitly present in the projects and works at the Biennale? To what extent was the Biennale directly curated, and to what extent is its consistency a consequence of the intelligently set structure and the main themes of every section of the exhibition?

Ana Dana Beroš: Koolhaas’ main condition was that he should be able to create a Biennale that would speak more of architecture than of architects. I presume that over the course of time an ambition had arisen to curate an exhibition that would use research as an architectural tool for understanding the built environment, and not necessarily present architectural projects. In each of the three components of the Fundamentals exhibition, the Koolhaas team tried to introduce a change in relation to the previous Biennales. Besides the exhibition Elements of Architecture, curated by Rem Koolhaas himself, the consistency of the entire Biennale directly results from the intelligent way in which the structure of every exhibition was set and conducted.

The exhibition that included my project, Intermundia, is a multidisciplinary work-in-progress exhibition project entitled Monditalia. I was one of around forty authors or teams presented, completely autonomous in my research work, production and installation set-up. In the end, I was given a Special Mention for a research project at the vernissage of the 14th Venice Biennale of Architecture in June 2014. Having interviewed Monditalia’s chief curator Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli for the show Reality of Space on Croatian Radio, I learned that Rem Koolhaas’ intention was to create a public space instead of exhibition space; to design an urban condition at the Biennale, instead of designing an exhibition. The role of Rem Koolhaas was not only curatorial, he also had the function of a cultural planner. Of course, he and his curatorial team took care of the exhibition content, but they also tried to pay attention to the entire creative reorganisation of the Biennale, they included all of its departments in an unique architectural event. The idea of reprogramming the Biennale, which was on for almost six months, during which the programmes of Biennale interchanged, including the Dance, the Film, the Theater and the Music Biennale, is something that in the future could become the new heritage of the Venice Biennale.